10 minute read

We all deal with a lot each day in our working lives. For many of us, our roles can be tough and complex already, let alone when we lay on top email overload, too many meetings, an unrealistic amount of work, organisational change, and difficult relationships! And if we’re not careful to look after ourselves, too much stress can tip over into burnout.

With more economic strife, in the UK and abroad, many organisations are cutting their cloth accordingly. This only puts further pressure on people. Doing “more with less” was already a mantra that I heard too many times over the years but we’re going to hear and see even more of this in the current climate. I talked about this on the HR Most Influential podcast When it comes down to it, what this really means is doing more with less people. This seems to have impacted the public sector more than most. While the bottom line might be saved, employee health pays the price.

In fact, stress and burnout is such a serious workplace issue that the World Health Organization (WHO) has designated burnout as an occupational phenomenon adding it to their International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11).

Not all stress is ‘bad’

In 1908, two researchers from Harvard University, Robert Yerkes and John Dodson, identified a causal relationship between arousal and performance. They found that performance increases with physical or mental arousal but only up to a certain point. This is called the Yerkes-Dodson Curve.

If you work somewhere where there is often low pressure, low challenge and little stimulation then you are likely to experience apathy. This is sometimes called ‘rust out’ – the opposite to burnout. And yes, there are people who experience this at work! Clues that people might be in this state are low motivation, low engagement and a lack of interest. There can be increased costs, such as dealing with underperformance.

At the other extreme, you have constant high pressure, high challenge, little to no support. It’s okay to be here for a short amount of time. For example, if there’s an emergency with a critical deadline then the adrenalin rush we get from that pressure can be helpful. However, this is the zone that can lead to burnout if people are here too long. Clues that people are here include physical (e.g., insomnia, stomach ulcers) and mental (e.g., easy loss of temper, depression). There are also increased costs for an organisation in this zone, such as rising sickness absence levels and having to backfill absences.

The ideal place is somewhere in the middle, with just enough challenge for us to feel stretched and enough support, should we need it. When people operate in this zone, we tend to see added value, such as through more engagement and ideas.

The main take-away from this is that not all stress is bad. We need enough of it to give us the adrenalin and the motivation to act. Psychologist, Kelly McGonigal, talks about this in her TED talk, How to make stress your friend.

McGonigal suggests we can benefit from stress in the following five ways, if we harness it in the right way:

- It can boost our energy levels – that spike in adrenalin, for example, can give us the edge we need to tackle that stressful task.

- It can get us in a state of flow – when we feel suitably challenged and we have the skills needed to do our job, stress can help us focus, be creative and problem-solve.

- It can make us more productive – the sweet spot of pressure/stress and having the right support can lead us to perform at high levels.

- It can help us to learn – some stressful situations are as a result of mistakes made, by ourselves or others. By taking the time to learn from that mistake, and planning ahead to overcome similar issues, we can rewire our brains to not react in a negative fight/flight/freeze way.

- It can boost our resilience – stress can act like weight training for our resilience, heightening our threshold for stress.

Take back some control

One of the things I’ve consistently found over the years is that what we focus on can play a big part in either reducing or heightening the effects of stress.

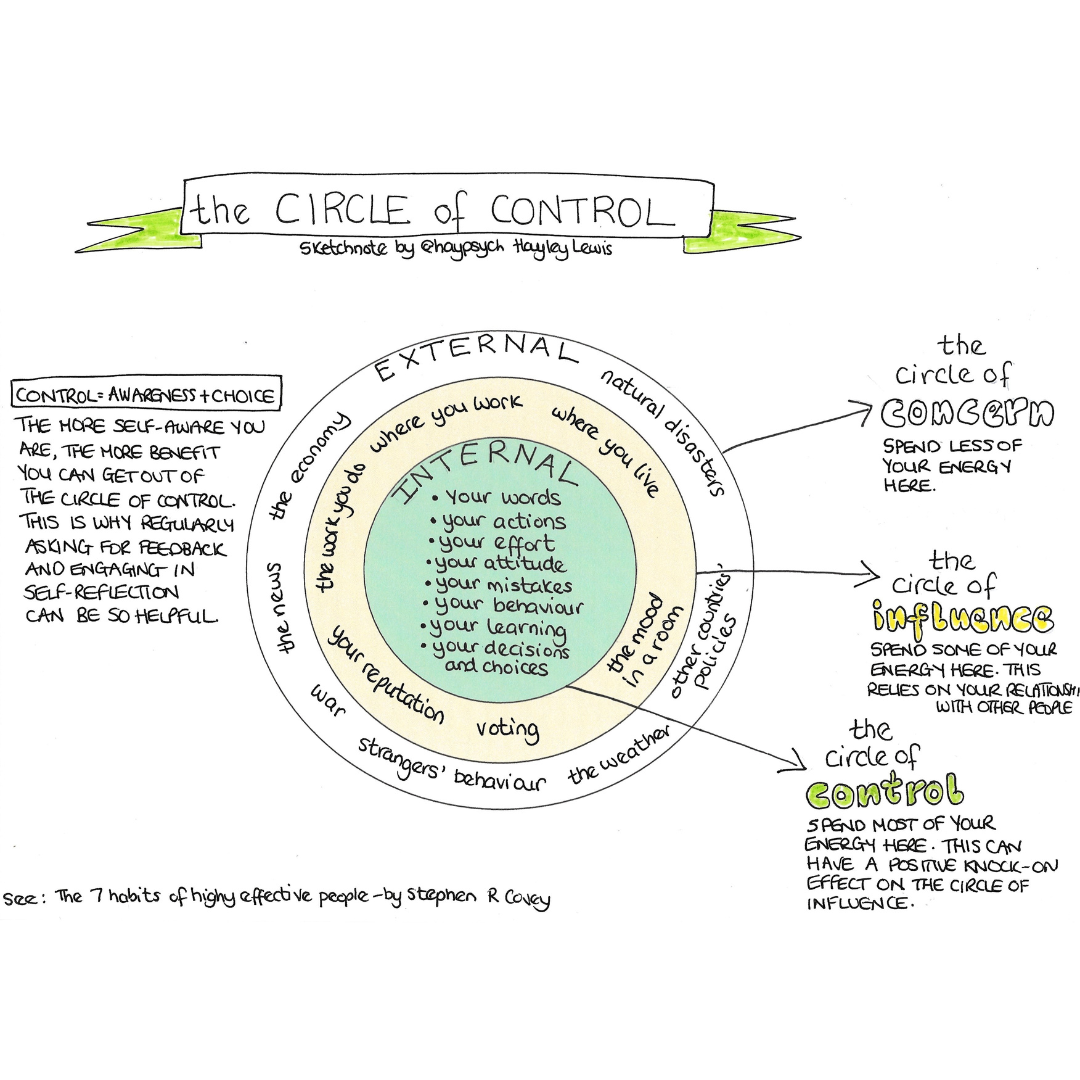

The Circle of Control is a framework I share with many of my coaching clients. It stems from the work of Stephen Covey and in particular, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. In the image below, you can see there are three circles.

The outer circle, known as the Circle of Concern, is where we should spend the least amount of our energy. These are things we have no control over. And so, worrying about these is a waste of our valuable energy and can lead to us feeling even more stressed. The next circle in, the Circle of Influence, is where we should spend some of our energy and relies a lot on our relationships with others. Finally, the inner circle, the Circle of Control, is where we should spend most of our time. The things we can control are our actions, our words, our decisions, and our learning. Focusing here can have a ripple effect outward on the other circles.

Set clear boundaries

One way we can take back some control is to set clear boundaries. This is particularly important in pushing back against a long-hours culture, along with too many emails and meetings.

Boundaries for your working hours

Working longer hours just doesn’t make good sense. For example, a Stanford University study suggests that our productivity drops significantly if we work more than 50 hours a week. And more than 55 hours sees our productivity drop so much that working any more hours would be a waste of time. The same study found that people who work up to 70 hours a week were getting the same amount of work done as their colleagues working 55 hours.

Cal Newport, in his book Deep Work, suggests setting a firm goal of not working past a certain time and then working backwards from this to prioritise and plan how you go about your day and week.

And boundaries around your working hours includes taking your lunch break. Breaks can help reduce our stress levels. A German study explored the impact of lunch breaks on well-being and performance. The researchers examined the responses of over 100 people, who responded to daily surveys which tracked their emotion, mood and performance. They found that the extent to which people felt recovered after a lunch break had a positive impact on their ability to complete tasks in the afternoon. Not only did lunch breaks help people feel more energised but it also helped increase engagement levels.

If taking your lunch break is something you struggle with, why not go with a colleague? A recent study suggests we’re more likely to take our breaks if we’re with others taking their breaks too.

Boundaries for your inbox

A study from Loughborough University suggests that the average employee spends around 29 minutes per day simply reading emails (this didn’t include writing them, processing them etc.). The same study suggests that for a company of around 3,000 people, that has a high email reliance, it cost around £9million per year simply for people to read emails.

However, it’s not just a financial cost. For example, one study found that when employees feel the pressure to check emails during their non-work hours, their health and wellbeing is negatively affected. Not just that, the same study suggests that this has a ripple effect, affecting the health and wellbeing of family members too. And yet another study suggests that when managers focus most of their time on their email they are less likely to be approachable and supportive to staff.

Setting aside some dedicated time for checking your inbox can make a big difference. For example, allocating 30 minutes in the morning, 30 minutes midday and 30 minutes at the end of the day. Then making sure to close your inbox and switch off alerts in the remaining times. Check out my 3 tactics to help you overcome email overwhelm.

Boundaries to protect your focus

We know that interruptions can impact our ability to do our work, particularly work that requires deep concentration. Every time we’re interrupted, we experience a surge in cortisol (the stress hormone) and this can then lead to a vicious circle. We feel stressed because we have so much on, we get interrupted, our stress levels rise, we then struggle to concentrate and so on. A study led by Gloria Mark suggests that recovering from interruptions takes up almost a third of an employee’s working day. The same study found that employees spent around 11 minutes on any given project before being interrupted. But it took the average employee around 25 minutes to return to the original task they were working on before being interrupted.

One solution is to block out periods of quiet, uninterrupted time. This means switching off your inbox and alerts and switching your phone to silent (unless you’re on call, for example). In a study of stressed and under-performing engineers, Professor Leslie Perlow found that constantly being interrupted by and subsequently helping colleagues solve problems was draining the engineers and taking them away from their own work. She helped them create dedicated windows of quiet time and interaction time which had a marked impact on their productivity and stress levels.

If you work in an office environment, then finding another place to do work during your quiet, uninterrupted time. For example, when I worked in a corporate role and I needed to do some work that required intense concentration, I would book a meeting room on a different floor for a couple of hours. I’d then take my laptop and go do the thing I needed to concentrate on.

The importance of social support

Adam Grant, in his book Give and Take, states, “…there is now a consistent and strong body of evidence that a lack of social support is linked to burnout.” And Mihaly Czikszentmihalyi reiterates this in his book, Flow: The psychology of happiness, when he says, “A supportive social network also mitigates stress: an illness or other misfortune is less likely to break a person down if he or she can rely on the emotional support of others.”

There’s a saying in the UK, “a problem shared is a problem halved”, and it’s fair to say that when we’re stressed talking it through with a sympathetic and supportive colleague can make a positive difference. However, if you’re the one offering a shoulder to cry on, be careful what you say. A recent study analysed how people dealing with stress responded to a variety of different messages offering emotional support. The researchers found that messages which gave the stressed person some form of validation appear to be more effective and helpful than those messages which were critical (“you should have…”) or diminish their emotions (“it’s not the end of the world…”). The researchers advise that instead of telling a stressed person how to feel (“don’t worry about it”) you could encourage them to talk about their thoughts or feelings so they can come to their own conclusions about what to do.

If you’re in a stressful and exhausting situation at work, one study suggests you could offset this by putting in place social support, such as meeting with friends for coffee, or going for a lunchtime walk and talk with a colleague, or asking for help and advice.

Try self-nudging

According to a paper from Cambridge University, it’s possible to strengthen our self-control by making simple changes to our environment, using a technique called self-nudging. The idea behind self-nudging is that we can design and structure our own environments in ways that make it easier for us to make the right choices and ultimately to reach our long-term goals. And so, if one of your main stressors is your inbox and you are always checking your email and responding to every single alert, you can try some self-nudging to take back some control.

The researchers outline four types of self-nudging tools and I’ve used the example of taking back control around your inbox:

1. Reminders and prompts. For example, set up specific appointments in your calendar for when you’ll check your email. Then close your inbox and switch off alerts outside of those times.

2. A different way framing things. For example, tell yourself that taking a break from work and cutting off the time you check emails acts as a buffer to your stress levels and can protect your wellbeing, as well as help you perform effectively.

3. Reduce the accessibility of things that can harm by making them less convenient or, conversely, making it easier to do the things we want to do. For example, delete the email app from your phone, making it harder to check your emails non-stop particularly outside of work.

4. Social pressure and self-commitments to increase accountability. For example, set goals to better manage your relationship with your inbox with a coach or a colleague who you check in with once a month to go through your progress.

Let’s do an experiment

Many of us start our day off well, with a clear to-do list. But how many of us put as much thought into how we end our day? Feeling good at the end of our working day can act as a buffer to our stress levels.

End the day well – an experiment for you to try

- Highlight 1-3 things you achieved.

- Plan the next day with a maximum of six items on your to-do list.

- Reflect on 1-3 things you are grateful for.

- Thank one person.

- Meditate for 5-10 minutes.

Do these five things at the end of each working day consistently for one month. Notice how you feel at the end of the month. What impact has it had on you? What about those around you?

STUDY REFERENCES

Becker, W. J., Belkin, L., & Tuskey, S. (2018). Killing me softly: Electronic communications monitoring and employee and spouse well-being. Academy of Management Proceedings, 18 (1).

Bosch, C., Sonnentag, S., & Pinck, A. S. (2018). What makes for a good break? A diary study on recovery experiences during lunch break. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91, 134-157.

Breevaart, K., & Tims, K. (2019). Crafting social resources on days when you are emotionally exhausted: The role of job insecurity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92, 806-824.

Jackson, T., Dawson, R., & Wilson, D. (2012). The cost of email interruption. Loughborough University.

Kerr, J. I., et al. (2020). The effects of acute work stress and appraisal on psychobiological stress responses in a group office environment. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 121, 104837.

Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: more speed and stress. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, April, 107-110.

Oliver, M., et al. (2021). Understanding the psychological and social influences on office workers taking breaks; a thematic analysis. Psychology & Health, 36, 351-366.

Pencavel, J. (April 2014). The productivity of working hours [Discussion paper No. 8129]. IZA and Stanford University.

Perlow, L. A. (1999). The time famine: Toward a sociology of work time. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 57-81.

Reijula, S., & Hertwig, R. (2022). Self-nudging and the citizen choice architect. Behavioural Public Policy, 6, 119-149.

Rosen, C. C., et al. (2019). Boxed in by your inbox: Implications of daily e-mail demands for managers’ leadership behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104, 19–33.

Tian, X., et al. (2020). How the comforting process fails: Psychological reactance to support messages. Journal of Communication, 70, 13–34

Did you find this post helpful? I’d love to know, so Tweet me, or drop me a note on LinkedIn. If you have any colleagues that you feel should read this, too, please share it with them. I’d really appreciate it.

I also have a monthly newsletter which is a compilation of blog posts, helpful research, and reviews of books and podcasts – all aimed at helping managers and leaders become more confident in handling a range of workplace issues. You can subscribe here -> SUBSCRIBE

If you liked this post, you might also like these:

The curse of middle-management: How to manage everyone wanting a piece of you

5 ways you can engage staff who are busy, stressed and at breaking point

Mindfulness at work: 6 things you can do to focus and manage interruptions

One comment