The technology industry is booming: in 2008, Microsoft was the only tech firm ranked in the world’s top 10 public companies by market capitalisation. In 2018, tech firms take seven of the top ten spots (Financial Times Global 500). Top graduates are more interested in joining Google than Goldman Sachs. Start-up ecosystems are exploding as entrepreneurs seek scalable fortunes.

Tech is often treated as a monolith; ‘Silicon Valley’ serves as shorthand for many genres of company. But no two tech companies are quite alike, and a reductive view of the technology industry belies the fundamental differences between today’s tech giants.

Close examination of the differences between major player’s business models illuminates why certain companies make certain decisions; how willing various companies are to sustain losses; why some companies are so preoccupied with margins, and how regulation could threaten some firms while protecting others.

In this post, I will provide a framework for categorising tech companies according to their business models. I’ll then describe the implications this framework has for competitive strategy. (In my next post, I’ll explore the implications for regulation, specifically privacy and anti-trust)

Platforms and aggregators

A useful schematic for thinking about tech business models is whether the company offers a platform, or an aggregator.

Platform businesses facilitate interactions between third parties and earn revenue by capturing a share of the value created in such interactions. Uber and Airbnb are the best examples of platforms: they catalyse transactions that wouldn’t have occurred otherwise. Amazon, Microsoft and Apple also employ platforms in their business models, in the form of online marketplaces, operating systems, application stores, and hardware that link buyers and sellers, or developers and users.

Aggregators also facilitate interactions between third parties, but actively intermediate and control the relationship. Alphabet and Facebook, for example, actively curate the content their users see, and carefully optimise advertising placements beside that content.

It’s not quite a simple binary: many companies’ services draw on elements of platform and aggregation business models. For example, Uber is a platform that connects drivers: but it also acts as an aggregator, as it actively controls the allocation of drivers to passengers and sets the terms of their interaction.

Business models

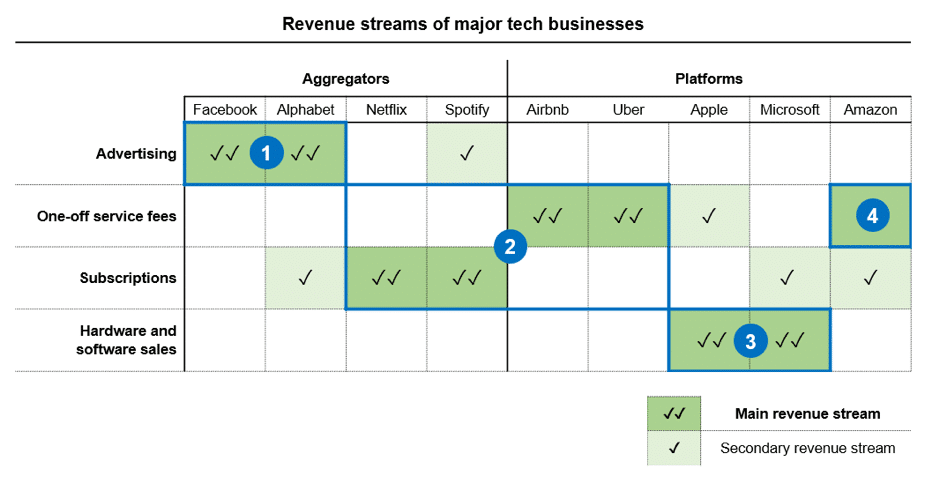

For simplicity, I’ll categorise revenues into four streams:

- Advertising revenues – where an advertiser pays for their content to appear next to content;

- One-off service fees – where users pay a fee in exchange for a service;

- Subscriptions – where service fees are paid on a recurring basis; and

- Hardware and software sales – where a product is sold.

It’s worth noting most businesses generate revenue from multiple streams through various product lines. For example, Alphabet, which makes most of its revenue from advertising, also sells hardware (the Pixel phone and Google Home). Amazon, which makes the majority of its revenue from sales and sales fees, also generates subscription revenue (Prime) and sells hardware (Kindle and Echo).

Organising these businesses by revenue type, and distinguishing primary and secondary revenue streams, shows four clusters of businesses:

1. Aggregators selling advertising

Aggregators that sell advertising derive competitive advantage from knowing an enormous amount of information about an enormous number of people, enabling unparalleled ad targeting. These companies benefit massively from network effects, which provide enormous moats: it’s incredibly difficult for competitors to overturn the monopolies Alphabet and Facebook have on search and social, which translate to duopolistic control of the online advertising market. For Alphabet and Facebook, competitors are so far behind the major threat to their businesses is regulation: something each firm grapples with in unique ways, as my next post will explore.

2. Aggregators and platforms selling services

These companies sell services by offering superior products and experiences, either in terms of quality or price. Fee-for-service business models are relatively easy to replicate, which makes it harder for such firms to build a ‘moat’ sufficient to deter fast-following competitors. For example, it’s easier for Lyft to match Uber in quality and price than it is for, say, Bing to match Google. The largest threat to service companies is customer churn. On a unit economic basis, a company incurs costs to acquire each customer (let’s say $100) and must ‘earn back’ the acquisition cost through revenue events (e.g. a $10 monthly subscription fee). If a customer stays for more than 10 months, they breakeven, and in month 11, generate net profit. If the customer churns before month 10, the company loses money. This is the reason such companies – Uber, Airbnb most notably – are willing to sustain enormous operating losses in order to grow: the returns of 100 million customers all reaching cumulative net profit far outweigh the returns of 1 million customers, and thus justify the early losses required to acquire large numbers of customers.

3. Platforms selling hardware and software

The best competitive advantage here is quality. Microsoft, once the world’s most valuable company, found success by selling top-line products that supported a thriving developer ecosystem: most notably, its operating system. Apple, now the world’s most valuable company, does the same through hardware, its operating system and its app store. For these firms, the major risk to revenue is simply that users stop purchasing their products, either defecting to competitors, or replacing their devices less frequently. You may have noticed that Apple has far more ‘blockbuster’ product launches to encourage continual upgrades, and positions itself as privacy-focussed in a way ad-selling aggregators do not. (Consider, for example, the new iOS privacy features announced in June). Like Facebook, Apple is also under regulatory scrutiny due to privacy concerns: but in the opposite direction. I’ll explain more in my next post.

4. Amazon – a special case

Amazon is somewhat a special case: it began as a more ‘traditional’ retailer, owning inventory and selling it through an online marketplace platform. Early on, it allowed third-party sellers to list their products on the same marketplace, for a fee that also included shipping, logistics and even warehousing services. Since 2016, Amazon sells more third-party items than its own inventory. Though Amazon is similar to firms that sell services via fees and subscriptions (indeed, it makes much of its revenue from third-party fees and Prime subscriptions) it is unique in scale and breadth, and its moat is enormous. Amazon’s competitive advantage is the economies of scale it’s achieved: these allow Amazon to enter new industries at very low cost points, attacking competitors’ margins.

As I’ve tried to show here, the technology industry is no monolith. Though Alphabet, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft and Amazon are often lumped together, they each have distinct strategies and unique competitive advantages. Understanding these differences is key to forecasting their impact on economic and public life. This framework also helps explain why each firm has caught regulators’ attention. In my next post, I’ll look at the risks each category of business poses to consumers, and discuss how regulators may seek to reshape the landscape.

Sam Smith worked in a top-tier management consulting firm for two years before taking time out for study. They write under a pseudonym to bring you honest reflections and insider information.

Images: Google Images